Postcolonial Mythologies

Firelei Báez at James Cohan Gallery

Firelei Báez

James Cohan Gallery

48 Walker St.

New York, NY 10013

March 5th – April 25th, 2020

Firelei Báez debuts her new, meticulously rendered paintings in her second exhibition with James Cohan Gallery. Báez is known for her devotion to researching and reclaiming diasporic histories through Afro-Caribbean and Latin mythology and iconography. Most notably, her fixation on “ciguapas”, the mischievous and feral female creatures that exist in Dominican folklore, serves to undermine the organized documentation of human migration and trade patterns. Báez’s latest works continue to confront the one-sided portrayals of human history by exposing the sinuous dispersion throughout a larger space.

Firelei Báez, Untitled (Drexciya), 2020. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 90 x 114 3/4 in. © Firelei Báez 2020. Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York.

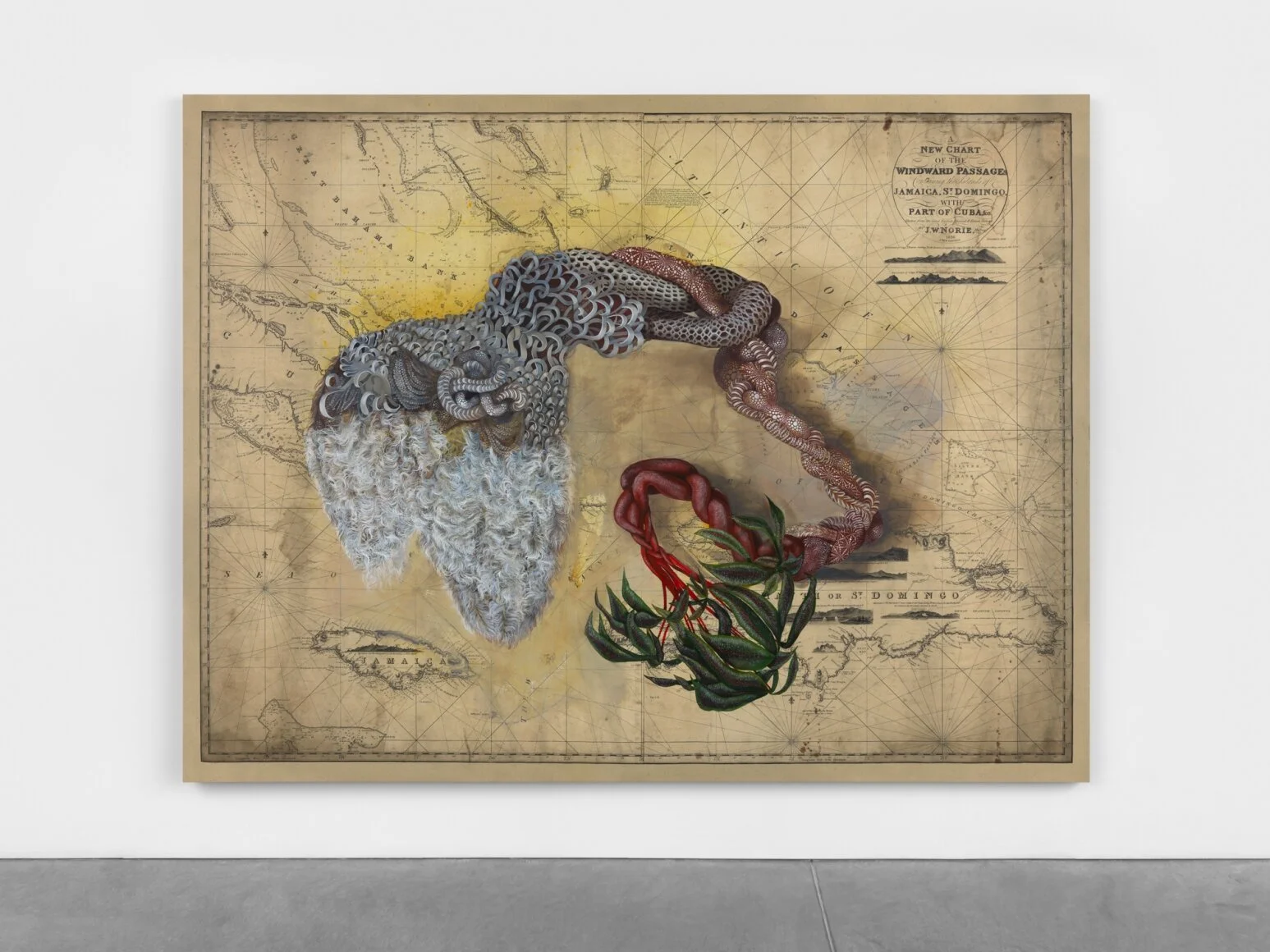

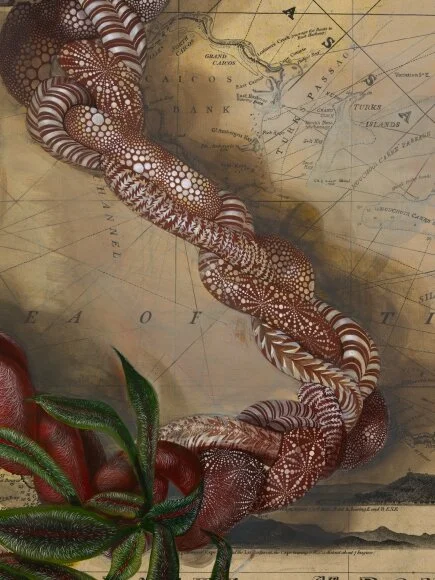

The exhibition consists of eight large-scale paintings on canvas, most of which depict archival reproductions of cartographical and statistical documents pertaining to the history of westward expansion into colonized lands. However, upon entering the gallery space, viewers are immediately faced with Untitled (Drexciya) — the only featured painting that isn’t based on a reproduced document. The oceanic gestures and color palette refer to the Middle Passage, one of the stages of the Triangular Trade route that forcibly transported African slaves to America and the West Indies. The name Drexciya is taken from the Detroit techno/electronic duo from the 90’s whose music and artistic philosophies served as a political criticism of racial inequalities. According to the sleeve notes of duo’s 1997 album, The Quest, “Drexciya” is an afrofuturist mythical country below the ocean with a society comprised of the unborn children of pregnant women thrown overboard off of slave ships traversing the Middle Passage. Báez embodies this action of black resilience and proliferation through her rendering of the seascape. She combines graceful strokes of oceanic motions with vaguely figurative elements that hint at both the acts of sinking to the floor and rising back up to the surface.

Firelei Báez, detail of Untitled (Drexciya), 2020. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 90 x 114 3/4 in. © Firelei Báez 2020. Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York.

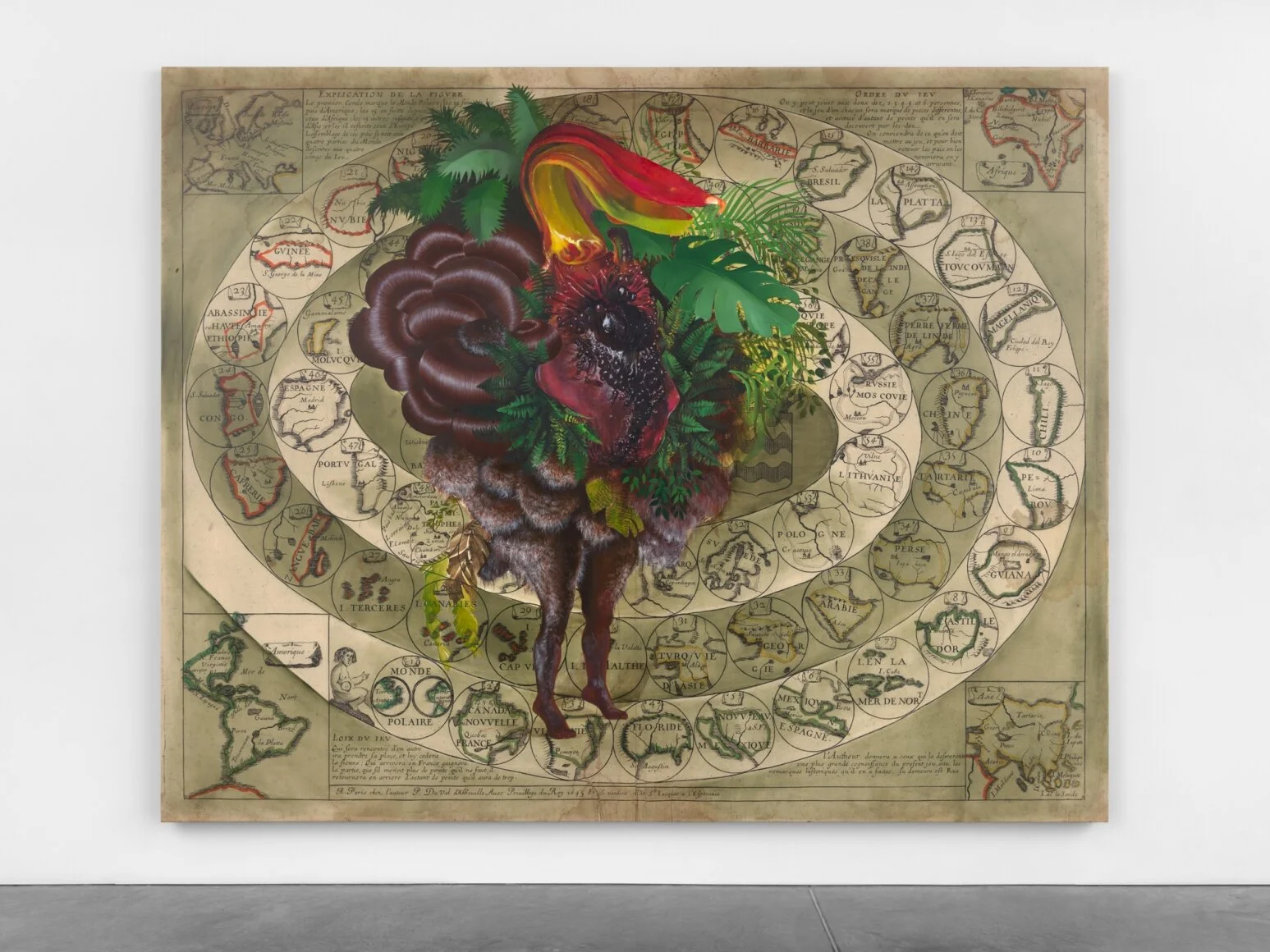

Báez is driven by her penchant for the mythological. She resists the vulnerable characterization of Black and Latin histories by consistently distorting colonially instilled hierarchies with folkloric references and cultural symbols. With her famous ciguapas, she continues to disrupt the notion of colonial assertions that European lands were of greater worth and stature than the rest of the world. With her painting, Untitled (Le Jeu du Monde), the florally embellished ciguapa offsets the center of the world as she stands powerfully over a canvas print of a French board game from the mid-1600’s. The game, Le Jeu du Monde, involved players rolling dice to move from the outer edges, which served as marked “corners” of the world, back to the center of the board: France. The ciguapa, typically referred to as a trickster, not only defies this unjust colonialist/capitalist “order”, but also indicates the abundant natural resources of the environment she resides in with her organic appendages.

Firelei Báez, Untitled (Le Jeu du Monde), 2020. Oil and acrylic on archival printed canvas, 105 x 131 3/4 x 1 5/8 in. © Firelei Báez 2020. Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York.

Báez’s defiance lends itself to a feminist narrative as her works emphasize the forced sacrifices of feminine power, tradition, and identity in a colonial landscape. In Untitled (Anacaona), the burning figure overlaid upon a navigational map of the Caribbean represents the Taíno cacique (chief), Anacaona, who was arrested and hanged by the conquistadors in 1503. Anacaona was revered as a successful leader of her kingdom, Jaragua, in the island of Hispaniola, and had overseen the co-existence of the Taínos and Spanish settlers under her rule. Anacaona is commemorated as an anti-colonial heroine in art and architecture across the Caribbean. Braided limbs and organic patterning represent her smoldering figure, clashing with the gridded, decisive ink lines of the ultra-intricate map behind her.

Firelei Báez, Untitled (Anacaona) 2020. Oil and acrylic on archival printed canvas, 96 3/8 x 127 3/8 in. © Firelei Báez 2020. Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York.

Báez has a history of working straight from archival resources and documents. Usually, she would work directly on found printed materials. In a previous interview regarding her solo exhibition, Bloodlines (2017), at the Andy Warhol Museum, Báez talked about her affinity for paper dynamic surface: “It’s very flexible,” she explained to the assistant curator at the Warhol, “It absorbs a humidity or dryness. It’ll expand or contract like our bodies often do.” But her departure from paper, and the confines of the documents she’s working directly on, is something I fully support. By converting these documents into prints on a canvas, Báez is truly able to re-appropriate and manipulate the content. In an act of power, Báez forces these documents to become conceptually flexible through their intentional republishing in a more functional medium over which she has control. The maps and data become hers to alter and re-represent, rather than existing as objects that she simply adds to.

Firelei Báez, detail of Untitled (Le Jeu du Monde), 2020. Oil and acrylic on archival printed canvas, 105 x 131 3/4 x 1 5/8 in. © Firelei Báez 2020. Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York.

There are many instances of conceptual continuity from her first exhibition at James Cohan Gallery in 2019, A Drexcyen Chronocommons (To win the war you fought it sideways). Báez created a deeply engaging mixed media installation that encapsulated broader Afro-Caribbean and Latin histories and cross-cultural meeting points through carefully selected materials such as blue tarps, wooden frames, selected books, plants, and incense alongside her earlier printed canvas paintings. Báez’s dedication to meticulous craft is a testament to her strength as a research-driven artist. Her second exhibition is a more concise exploration of materiality and its importance to the untold histories she strives to represent.

Firelei Báez, detail of Untitled (Anacaona) 2020. Oil and acrylic on archival printed canvas, 96 3/8 x 127 3/8 in. © Firelei Báez 2020. Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York.

Báez’s new paintings are captivating even for those who aren’t necessarily aligned with the subject matter. The paintings are fastidiously but lovingly rendered with a rich palette and incredible presence of the hand. Another painting of hers is also available for view at James Cohan Gallery’s space, booth 922, in the Armory Show. Be sure to have a look if you intend to drop in for one last visit to Pier 94 as Armory Week comes to a close. Once again, Firelei Báez’s scholarly approach to the retelling of the past has us looking forward to the pliancy of the future.