Love, sex, sexuality… sometimes connected, sometimes not…

Remembering Robert Heinecken

I have always believed that to understand something, one must really need to try to understand it in relation to the time in which it happened. In this spirit, one would have to imagine the time before the internet and easy access to information:

A young and naïve undergraduate opens the January 1968, No. 1 issue of Camera magazine and reads the following statement:

“We know only what we do, what we make, what we construct: and all we construct, are realities. I call them ‘images,’ not in the Plato sense (nominally that they are only reflections of reality), but I hold that these images are reality itself and that there is no reality beyond this reality except when in our creative process we change the images: then we create new realities”

The student then turns the page, to reveal the work of a photographer named Robert Heinecken, who creates photographs about something, not of something, and the student’s life is changed forever.

That was my experience in 1968, and it was a massive confirmation of a direction in which I had been headed for some time. It was a life-altering event. All the aesthetic and conceptual ideas that I had been exploring were validated. My work — although crude at the time — was vindicated, and not just by Heinecken’s work, but by the work of the other photographers in the issue. It was an amazing revelation to me because I was working almost in isolation, with no fine art photography contacts. I had no one to bounce ideas off of or talk to and, perhaps more importantly, no one with whom to critique.

I would later work and study with Heinecken at UCLA, as well as with other outstanding photographic artists/teachers who shared similar aesthetics; in particular Karen Truax, Judith Golden and Joyce Neimanas. They all helped to philosophically and conceptually develop my unique aesthetic.

I will admit that the similarities of our interest in ‘found’ or, my preferred term, ‘societal’ images did cause some unavoidable and sometimes negative comparisons. I was fully aware of the inevitability of this, but chose to be close to his intellectual influence regardless. From an early date, I held the philosophy that one had two choices in life: to hide something or to emphasize it. I chose to emphasize our similarities and to grow, rather than be diminished, by them.

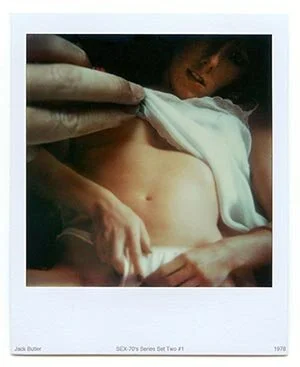

For the sake of this discussion, I think it would be interesting to briefly compare a few pieces from two series that to exemplify this aesthetically twinned relationship. In 1978, while working on my MFA at UCLA, I used the Polaroid SX-70 camera to produce a body of work that dealt with cyclic fantasy experiences as they related to sexually-based ‘societal’ images. This was just one of many series I produced about this concept. It was simply a continuation of an ongoing exploration.

Heinecken was on leave from UCLA, teaching and working in Chicago. Unbeknownst to me, he was also working with the SX-70 camera, and it was only much later that I was privy to the parallels in our mutual exploration. The bodies of work are quite dissimilar in their intent but also quite similar their orientation. This similarity was inevitable, based on our aesthetic interests, but it was still remarkable in its perfunctory appearance.

Heinecken’s pieces are from his He/She series, directed by their selection and juxtaposition to written text. A narrative of handwritten dialogue between a man and a woman of an off-hand conversation is raised to a new level by their association with SX-70 images. This visceral reaction is heightened by the ‘instant’ gratification associated with the SX-70 picture making system. This system was designed primarily for making ‘snapshots,’ usually implying some degree of intimacy between the photographer and the subject matter. By choosing to leave the recognizable SX-70 borders on the prints, Heinecken references his process. The images in these pieces range from associative in nature to direct observation. The ‘meaning’ is derived from one’s interpretation of the relationship between the storytellers, the images shown, and the text. The content is intended to form a mental and sensory experience in the viewer, perhaps even relating to one’s own personal experiences. I have also always been intrigued by the underlying sense of humor in these images; they always made me smile when reading and viewing.

At virtually the same time in Los Angeles, I was producing a series called the SEX-70’s series. It utilized the same picture making system as Heinecken, but in a very different manner. I set up my subject matter to directly reference one activity and source. I then staged an interactive pose, utilizing my own hand, and photographed it with an SX-70 Camera. I also used the complete SX-70 image to reference my process.

The images shown here are from the SEX-70’s – series 2 group. These images represent the cyclic nature of experience, fantasy and voyeurism. They also deal with the concept of veracity as it relates to the photographic image; a concept that has always been a re-occurring theme in my work. The original image existed in readily available commercial magazines and its intent was to induce some sort of sexual fantasy based on the activity shown in the image. The introduction of my hand to simulate the implied activity then ‘personalizes’ the activity. The viewer becomes the participant ‘visually and mentally.’ This participation could be either positive or negative depending on one’s personal philosophy. As the images are ‘read’ and ‘interpreted’ by the viewer, the cyclic aspect is completed. The cycle from the original pose, to the photograph, to the magazine (intended for fantasy) to the re-photograph by hand, (to heighten implied fantasy) to the personalized experience (mentally); becomes entangled with the veracity of the SX-70 photograph, which represents and is consistent with ‘instant gratification’ or ‘realness’. I would also hope that there is a certain amount of humor evident in the brazen nature of the activity.

So, at virtually the same time, Heinecken and I were both producing work using the SX-70 Camera and its implied instant believability, and we were totally unaware of the other’s work. Both bodies of work dealt with sensual and sexual situations, and both required the viewer to complete the experience.

Now the interesting thing about Heinecken as a teacher was that he never showed his students his work, and he never imposed his philosophy — or any philosophy —into the pedagogical process. He always encouraged his students to develop their own personal manner of image making, regardless of aesthetic. So one never knew if one’s visual explorations were intersecting with Heinecken’s or not. This ‘absenting’ of his personal philosophy was, in the end, one of Heinecken’s greatest strengths as a teacher.

Jack Butler has been a distinguished Artist/Photographer/Educator and showing Nationally and Internationally for over forty years. Among awards he has received, COLA Grant from the City of Los Angeles, NEA Visual Artists Grant and two Polaroid Artists Fellowships. He is now a Professor Emeritus from California State University Los Angeles and living and working in Gig Harbor, Washington.