The School of Survival

Learning with Juan Downey

Juan Downey, Being Alone, Sharing, from the series Mi Casa en la Playa, 1975, colored pencil and graphite on paper, 33 1/4 x 46 3/8 inches. Image courtesy of the Estate of Juan Downey.

Comprising little-known works by the Chilean-born artist, The School of Survival: Learning with Juan Downey highlights Downey’s role as an educator, with a decided emphasis on his thinking regarding architecture and ecological sustainability. The specter of ideology haunts Downey’s pedagogy, just as it haunted the social practice of his generation. In seeking to realize a better world, the baby boomers confined themselves to a purview where society could be rationally understood and controlled. But a world without accidents and error is hardly more than a simulation.

The works on exhibit can rightly be called ephemera; these include diagrammatic illustrations for lectures, handwritten scrawls in notebooks, and photo documentation of friable sculptures (more like “happenings” than agitprop). What comes out of all this is less a sense of the person Downey was than the particular way he had of teaching.

Juan Downey, Life Cycle: Soil + Water + Air = Flowers + Bees = Honey, 1972, graphite, colored pencil, and collage on paper, 40 x 60 inches. Image courtesy of the Estate of Juan Downey.

One work that immediately caught my attention was the diagrammatic Life Cycle: Soil + Water + Air = Flowers + Bees = Honey (1972). This piece illustrates, quite literally, both the radical and the traditionalist aspects of Downey’s practice (traditionalism, of course, being what the political right parasitically clings to). When I first saw this work, I fixated on what was explained to me as a conservation error: namely, the way a collaged figure (a caucasian male, possibly cribbed from a magazine) seems to lose his hand in a vegetal system of hothouse life. This literal disarmament spoke worlds to me about the cultural biases underlying even the most progressive political programs; biases which ultimately castrate the universality of social change.

Looking at Downey’s work today, it might seem to status quo apologists that he was simply wrong. Yet art never simply wrong or right; and the idea of a social architecture rooted in the synthesizing potential of digital technology is as utopian today as it was forty years ago. The difference is that the revolutionary hopes of Downey’s generation, and the technologies they saw as the tools of their liberation, have all been co-opted by corporatocracy.

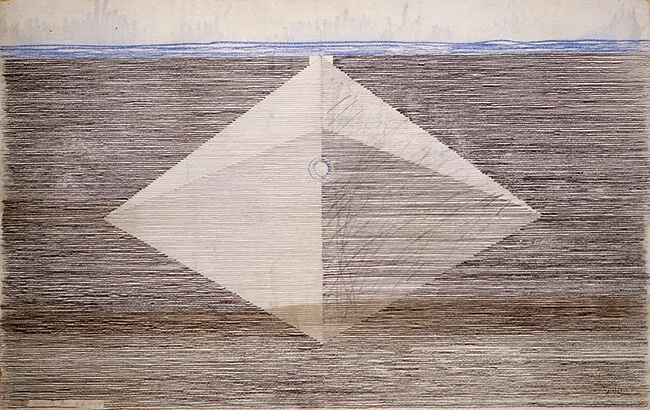

Juan Downey, Accurate Base and Height (Cheops Pyramid), from the series Mi Casa en la Playa, 1975, colored pencil and graphite on paper, 33 1/4 x 46 3/8 inches. Image courtesy of the Estate of Juan Downey.

As an offshoot of Downey’s influential oeuvre, The School of Survival offers a glimpse into the mind of a politically astute artist. The importance of the show lies in the way it conversationally reveals his creative aspirations, hitherto only known to his students and collaborators. Downey’s school of thought still communicates an important lesson regarding how to approach social space in a non-colonizing way; and one leaves the show wondering to what regions of the world his methods might still apply.