Generative Death in The Ruins

Cyborg theory, pioneered by theorist Donna Haraway with her 1985 essay A Cyborg Manifesto, relishes the breakdown of boundaries between humanity and artifice. The cyborg, to Haraway, questions the dualisms that structure Western thought by presenting a new mode of existence outside of binaries such as male/female or nature/artifice. Media artist Claudia Hart cites Haraway as an influence on her show The Ruins at bitforms gallery. Like Haraway’s cyborgs, Hart’s artworks defy simple categorization, existing simultaneously in virtual and physical spaces and drawing from sources as disparate as Matisse, memento mori still-life, and video games.

Claudia Hart. Photo by Leslie Silva.

Claudia Hart, currently a professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, has had a long and varied career in the arts. Her work has been collected by major institutions like the Met and MoMA, and she has worked with organizations like Eyebeam and BRIC. Arcade Project’s M. Charlene Stevens sat down with Hart to discuss her work’s place in art history and why this eurocentric and patriarchal history needs to die so that new ways of seeing and thinking can potentially thrive.

Installation view of The Ruins at Bitforms Gallery. Image courtesy of the gallery.

Arcade Project: Part of Andy Warhol’s 2018 retrospective at the Whitney that resonated with me was the gallery filled with larger-than-life projections of Andy’s screen tests. It hit in that area between still image and video—they were movies, but the space felt like a portrait gallery rather than a cinema. I see something like that in your work, where it is almost a moving, animated image, but it presents itself as a still with only slight motions.

Claudia Hart: Paradigm shifts that come from technologies of representation change the way we imagine, react, what we categorize as real, and what we think of as the role of representation. When we moved from painting to photography, painting changed, as did ideas about industrialization, what's authentic, what is a copy, what is the role of representation in art. When I was young, I was interested in the Warhol movies because they were sitting on that cusp. The Empire State Building and his screen tests were playing with portraiture or landscape to create situations in which nothing is happening, but everything is happening. It was about time. He was moving out of cinematic narrative time.

Claudia Hart, The Orange Room, 2019. Video animation (color, sound), media player, screen or projector, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the gallery.

AP: This goes back to the tension between painting and photography: after the invention of the camera, there was nowhere further to go with representation.

CH: Right. Realism stopped being the job and was taken over by photography. Then painting tasked itself with being filled with the higher real: Suprematism and modernism.

AP: I think that photography freed painting from realism so it could become so much more. It released it from its trap: that it was responsible for representing us and finally could take it to other levels. What about the moving image, though?

CH: With painting, I was interested in Matisse because he was at the beginning of copyright, and that allowed me to think about all these things I'm interested in, including photography, the age of mechanical reproduction, how photography changed our idea of reality and what is real, and how photography created painting as authentic experience, not as representation.

It was authentic because it was not representing reality but expressing the artist. It came full circle when we started to have people, like Warhol, whose whole thing was based on photography, silkscreen and mechanical reproduction. He brought the idea that you didn't need touch to be authentic, you needed a concept and the conceptual structure that was imposed by the artist was the mark of the art, not touch.

With Matisse, he put the flowers on the table, and they became part of the wallpaper: it's this repetition of images within images, windows within windows. My idea is that you would have levels of screens, the monitor in the room, which has the picture of the picture, the simulated space, a recursive system. It uses itself to build itself and this idea of recursivity is a motif you see in digital art that appears all the time because it's in the nature of the medium.

Claudia Hart, Big Red, 2019. Video animation (color, silent), tiled monitors or projection on stretched screen, computer or media player 90 x 63 x 1.5 in, 5 min, video loop. Edition of 1. Image courtesy of the gallery.

AP: We went from taking something that's 3-D to 2-D in modernism and then you're looking back at modernism at something has been flattened and then you're putting the third dimension back, right?

CH: 3D is marked by a convergence of old-fashioned perspective. It's actually five-point perspective: the ceiling, the floor, the sidewalls, and the back wall meeting the camera. You cannot enter the space of 3-D without entering through the camera, like a GoPro. Your head becomes a camera. Your body can move but you are a cyborg.

AP: You are an extension of the camera?

CH: Yes, and that's the Donna Haraway idea. With 3-D you can only render it out through the camera, and the space behind the viewpoint is perspective. You are a cyborg, your head is a camera; that is the construction. In the first phase of my work, I was obsessed with Haraway because of everything she decided about the cyborg, both in terms of gender politics and her utopian view of it and the animal, machine and nature merging together.

AP: That's a good segue, because there's some focus on beauty and nature in the digital space of your work.

CH: I was bringing together nature with a computer simulation and that was why I simulated movement, because when you sit in nature its stillness is not still: everything is moving at slightly different rates. The leaves on the trees, the grass and the flowers… everything's throbbing slightly.

AP: It's like you're achieving what the impressionists were after with things that are always moving and throbbing and it becomes a blur, but you're achieving the effect in a whole different way.

The show’s titular piece, The Ruins, is a three-channel video that resembles a first-person video game or a maze. Could you elaborate on some of its influences?

CH: The idea of The Ruins is about the labyrinth in the romantic garden, where you're supposed to be meditating on failure, the end of history, collapse and rebirth, the Nietzschean idea of eternal return. The sublime is the idea that failure is generative, that things have to die in order for something else to be reborn, and labyrinths are part of that idea. It's cemetery architecture.

AP: Are you saying that these things need to die so that something can come out that's more than European and male?

CH: That’s right. The generative death was that creativity comes from death, and that you needed things to die in order to make a new thing. But you're also building on the pile because you can never make a new thing. You're always stuck with history. And that's sort of the point of it, right? So yes, generative death.

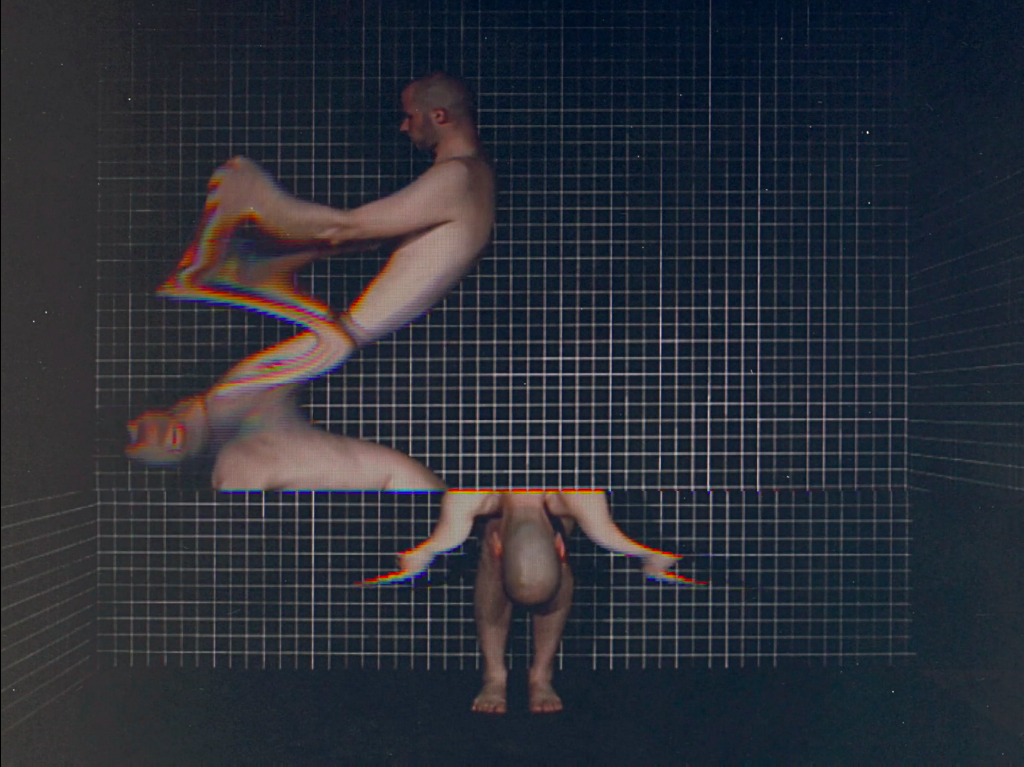

Claudia Hart

The Ruins

September 10 to October 24, 2020

bitforms gallery

131 Allen Street, New York, NY 10002

Cover image: Still from The Orange Room, 2019. Video animation (color, sound), media player, screen or projector, dimensions variable.