The Stem, The Flower, The Root, The Seed

A Conversation with Nyeema Morgan

The Stem, The Flower, The Root, The Seed is Nyeema Morgan’s solo exhibition at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, on view through January 29, 2021. Morgan plays with the slippery quality of text to lead our minds astray. Her ongoing series of works Soft Power, Hard Margins, Like it is: Extraordinary Women and The Stem, The Flower, The Root, The Seed, and others, explore textual references to narratives of specific and mythological individuals and the alacrity with which the two can be confused. Morgan talks about her use of installation, both for text and sculptural works, as a means of interrogating the positions of artist and spectator, and to question who is receiving what from whom.

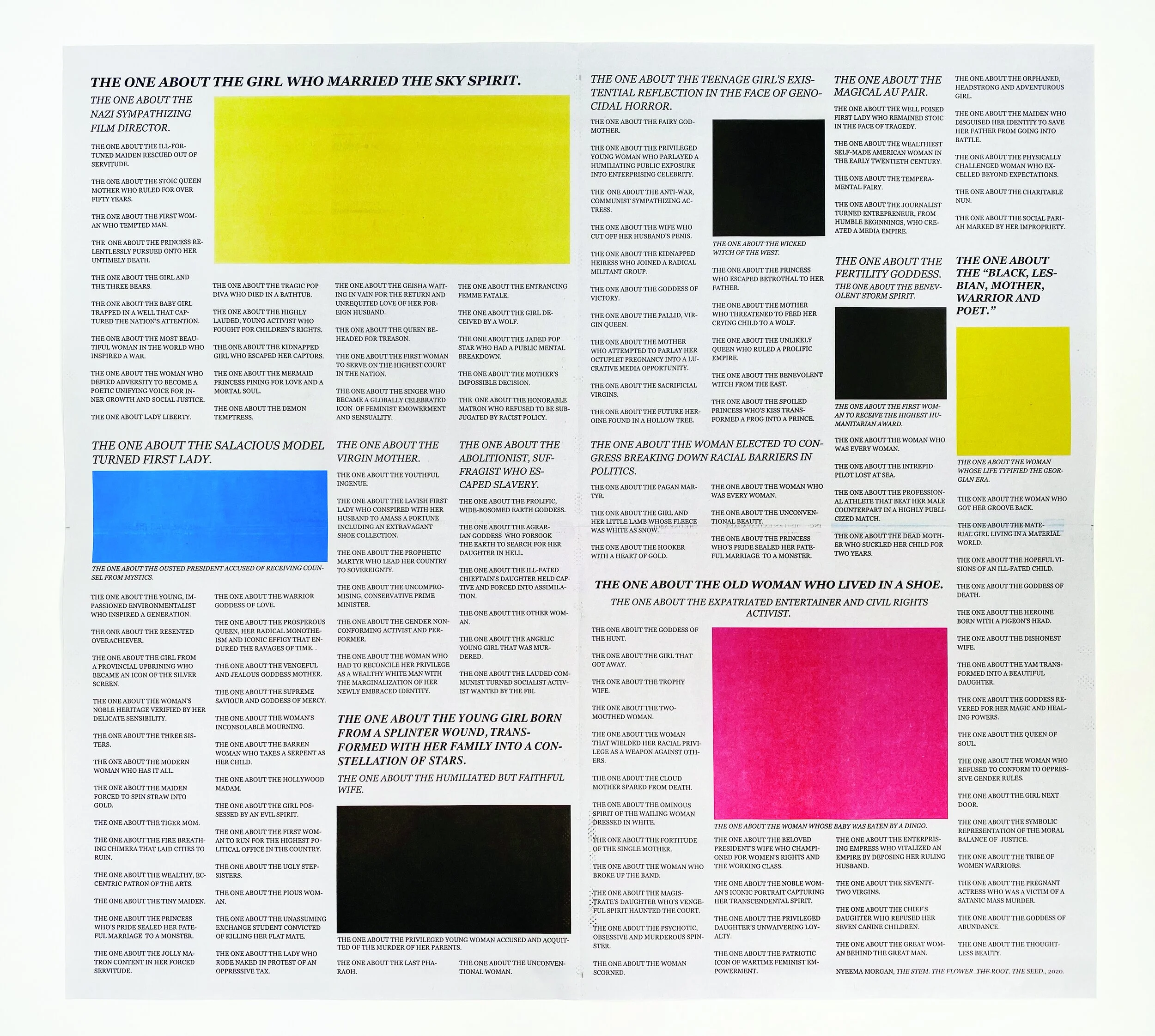

Nyeema Morgan, THE STEM. THE FLOWER. THE ROOT. THE SEED., 2020, mixed media installation: wood dowel, resin, broadsheet newsprint, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of The Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, Boulder, CO. Credit: Wes Magyar

William Corwin (Arcade Project): What are your thoughts on exhibiting you work in the time of the pandemic?

Nyeema Morgan: It’s important to me that the viewer shares space with the work: that you can experience the work in real time rather than in images or virtually. So, the situation isn’t ideal, but what can you do? There are a few works in the show; a work called: The Flower, No.4 which is white vinyl text on white walls. There are about eighty of these texts interspersed throughout the exhibition, and because it’s so discreet you don’t really notice them until your body shifts in the space and the light hits the wall and the vinyl—then you start to glimpse the text.

AP: What work is in the current exhibition at BMOCA?

NM: When I was invited by curator Rose van Mierlo I was in the midst of making a large body of new work called Soft Power. Hard Margins. for a solo show at table (an artist-run space) here in Chicago. The BMOCA show is a part of a year of programming related to the 2020 centennial of Women’s Suffrage. I wanted to bring together a group of works that address the themes of subjectivity, objectivity, and power: which are present in much of my work. I decided to do a smaller offshoot of Soft Power. Hard Margins focusing on the work of women artists—seminal works within the art historical canon.

Nyeema Morgan, The Flower, No. 3, 2020, broadsheet newsprint, 22.75 x 25 in. Image courtesy of the artist.

Then there’s the vinyl text that I mentioned that begin with “The one about…” What follows “The one about…” is a reference to a female figure, mythological, fictional or historical. “The one about the woman who got her groove back,” or “The one about the dishonest wife:” “The one about the salacious model turned first lady,” is right along with text referencing Shirley Chisholm. It steers away from the specific narrative and subjectivity of those figures and points more to a type of story. All of these stories that are passed on to us throughout our lives. I sat writing these over a period of a month trying to extract them from memory. In the midst of recalling them, I was questioning these Jungian archetypes which most conventional stories about women abide by, but also archetypical variations related to stories about women of color or queer women. How, or which, types of these stories enter into conventional storytelling.

AP: I wanted to talk to you about your relationship with words. In Like it is, you’re dealing with the printed text; how are you visualizing the word as an aesthetic object versus the “read” meaning you’re conveying?

NM: Yeah, that’s crucial in all of my work. I’ve always been incredulous. I was taught to interrogate everything— to peel away the layers. Thinking about how language is used was an integral part of my survival training and later thinking about its form, playing with its form, subverting its legibility became a part of my practice. In Soft Power, Hard Margins there is this antagonism between text as image, the image, and the object: as a space for the viewer to have to negotiate and to be pulled back and forth. Thinking about text aesthetically is a way, for me, to slow down our reading—something we do very automatically, and to question how language is represented and how we make meaning.

Nyeema Morgan, Soft Power. Hard Margins. (1973-1976), 2020, mixed paper media, cast resin, composite gold foil, LEDs, 18.5 x. 15.5 x 3 in. Image courtesy of The Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, Boulder, CO. Credit: Wes Magyar.

AP: The voice that you present in your work using the phrase; “The one about…” which makes you think of a comedian, and then “Permission to…” is confrontational and funny. “Permission to…” is also weirdly military, as in always being forced to ask for something from someone. Can you talk more about that voice?

NM: It’s pretty glib. That dominant voice at the center of American culture. The author is that royal “we” that we are supposed to empathize with. Then the permission; the “Permission to…” was inspired by a text by Adrian Piper. Piper wrote an essay in response to a racist exhibition title by a white male artist in New York in the 70s. In the essay —Power Relations Within Existing Art Institutions (1983) she wrote: “Freedom of expression is not a right it is a permission granted by the state.” I started to look at these works throughout history that have been extracted bearing high cultural value— sanctioned works. Thinking about how that work functions in the service of our contemporary life. When your aunt, or whoever, looks at Richard Long’s A Line Made By Walking (1967) and says something like “well this isn’t art, he’s just walking through the grass;”. Your aunt can access, through the work, the same questions that occupy the work itself. Whether something as banal as walking can be transformed into an aesthetic work. “Permission to…;” it’s a bit antagonistic, you’re being granted the right to a form of expression or belief or attitude which is anathema to the autonomy of a free person.

Nyeema Morgan, Untitled, No. 1 (I, Rhinoceros), 2014, cast and painted resin with found objects, 18 x 8 x 49 in. Image courtesy of the artist and Grant Wahlquist Gallery, Portland, ME.

AP: In your practice you focus on text, but you also make pieces like Untitled No. 1 (I, Rhinoceros) (2014), which is a sculpture. What’s that piece about?

NM: As I move through different works, there are moments where I’m trying to reconcile text and image, object and image, object and text. For that work, Untitled No. 1 (I, Rhinoceros), the reference is to Dürer’s Rhinoceros (1515). I had been attracted to that work for a long time but it wasn’t until recently that I realized the story of its conception was more important to me than the object— the print. Durer was commissioned to create a representation of this exotic animal, but it wasn’t made from firsthand experience, but from a story. Someone wrote a description of the rhinoceros; someone who had seen it. Once the rhinoceros had been imported to the region and people could actually see this animal, more accurate representations supplanted Dürer’s. I was grappling with questions of representation and authenticity, and also my relationship as an artist to an audience, to a viewer. I had questions about my relationship to that audience. I make my work: I need to make my work. It is important that it has a life outside of my making and outside of the studio. I was asking myself: what is it that I need from the viewer? I was also wondering, “is there any reciprocation?”. When a person walks across the threshold of a gallery or museum, what is it that they anticipate receiving? Untitled No. 1 (I, Rhinoceros) is where I wanted to implicate myself in the relationship between artist and viewer—so those are my cast hands holding these found vessels which were mass produced lamps I suppose. I used to have a studio in Industry City in Brooklyn: in the mid aughts there were a lot of manufacturers there and sometimes they’d trash a shit-ton of mass-produced things. I pulled these absurd objects because they reference to old world objects with their classical motifs, but they’re grossly mass-produced objects. Again, reproduction and materiality runs heavily through this work as it does in much of my work. The castings of my hands—there are subtle variations in how they’re holding these identical vessels and they’re installed at a specific height where there’s ambiguity with the gesture in terms of whether it’s an offering or a receptacle.

Nyeema Morgan, THE STEM. THE FLOWER. THE ROOT. THE SEED., 2020, mixed media installation: wood dowel, resin, broadsheet newsprint, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of The Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, Boulder, CO. Credit: Wes Magyar

AP: Is ambiguity a recurring theme in the sculpture?

NM: Yes, especially in the piece at Boulder, The Stem, The Flower, The Root, The Seed. The installation of hands are displayed in a way where they could be read as a defensive gesture, or it could be an offering. The broadsheet newsprints supported by the wooden dowels, The Flower, No. 3, which are available for the viewer to take, could also be read as flags of submission. There’s ample room for uncertainty, aesthetic pleasure, self-reflection and questioning.