The Tragedy of Comedy in I, Tonya

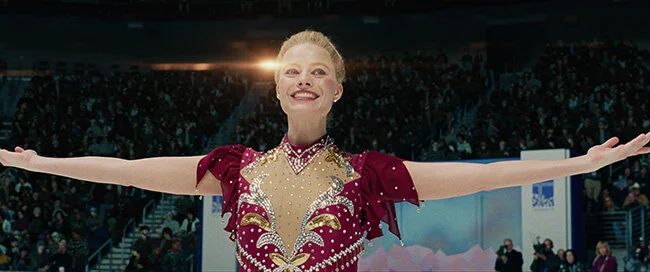

Tonya Harding (Margot Robbie) after landing the triple axel in I, TONYA, courtesy of NEON and 30WEST

I first learned about the film I, Tonya (Dir. Craig Gillespie) when I saw an eye-catching advertisement for it at the Arclight Theater in Hollywood, which featured a life-size cardboard cutout of actress Margot Robbie as Tonya Harding, dressed in a competition-style figure skating dress and holding a lit cigarette with a tough-girl expression on her face. I didn’t know much of anything about Tonya Harding at the time: I was young during her rise and fall and my sports history is fairly lacking. But her posture and expression caught my interest, and I went to view the film despite not knowing much about her.

The film is narrated by several characters in interview segments and in voice over. These characters, including Tonya, her partner, Jeff Gilooly (Sebastian Stan) and her mother, LaVona Golden (Alison Janney), among others, tell conflicting stories about events throughout Tonya’s life, leaving the audience wondering which narrator is most trustworthy. This stylistic choice allows the characters to give their commentary on events as they unfold, creating an emotional connection with Tonya and allowing those in conflict with her a means of giving their impressions directly.

Early in the film, Tonya and her mother tell conflicting stories about whether or not LaVona was abusive towards her daughter. LaVona confesses to having hit Tonya on only one occasion and the scene plays out for us: We see LaVona holding a very young Tonya by the arm in the ice rink bathroom and striking her repeatedly with a plastic hairbrush. The bathroom door opens and LaVona looks at the stranger and delivers a one-liner to dismiss the violence that she just inflicted upon her young, vulnerable daughter. And it worked to diffuse the situation, at least in the theater where I viewed it. The audience laughed. It wasn’t a roar of laughter, but there were snickers and giggles rising throughout the auditorium.

LaVona Golden (Allison-Janney) and her pet bird in I, TONYA, courtesy of NEON and 30WEST

Depictions of abuse in Tonya’s life are frequent in the film. We see her mother refuse to let her leave the ice to use the restroom while practicing, forcing the young girl to wet herself. Her mother’s cold reaction is to tell her to “skate wet.” This extreme humiliation and emotional abuse was, once again, met with the audience’s quiet laughter. It was unclear to me why at the time, but after just a few scenes something had become clear: The audience around me thought it was funny when bad things happened to Tonya. This was a dangerous precedent to set, since the movie was about to show us more than a few things that are decidedly not funny.

Women who have survived domestic abuse are expected to be sensitive. They are expected to be delicate and careful when talking about their experiences. Traumatic stress is frequently displayed in the media as a woman breaking down into tears when she gets to the most poignantly sad part of her story. There’s another level to this expectation of sensitivity, though. Women in these situations are expected to talk about their experiences in a way which is sensitive to the listener, or in the case of a film, the viewer. They are to share their experiences in a way which protects others from having to actually feel the effects of them.

Robbie’s version of Tonya is not sensitive; there’s no room for softness in her world. She had to become hard to survive, and as a result, she talks about the abuse in the exact way in which women are conditioned against: She is candid and direct about it, sometimes coming across as flippant. She makes the reality of her situation stark and unavoidable instead of talking about the abuse in vague terms and with a sense of reverence. It is real and it’s important. But it isn’t funny.

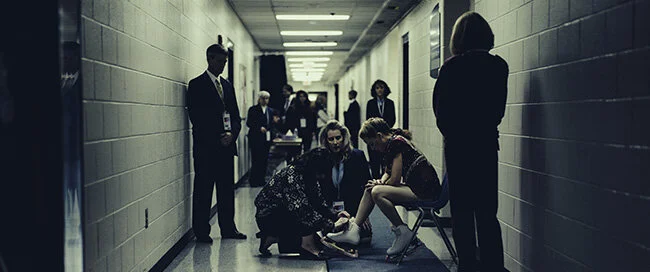

Tonya Harding (Margot Robbie) before competing at the Olympics in I, TONYA, courtesy of NEON and 30WEST

The words “black humor” are used to describe I, Tonya in almost every review I’ve read, and it’s not an inaccurate choice. Some parts of the film are truly, laugh aloud funny, especially anything involving Shawn, Jeff’s friend who was instrumental to the organization of the attack of Kerrigan. But much of what people responded to as humor were depictions of violence and emotional abuse that were shared without the seriousness and sanctity they are used to.

An ad I later saw online shed some light on this reaction. It showed the zaniest moments of the film in quick succession, followed by bits of critical praise. Every source said the same thing about the film: simply the word “Hilarious.” This marketing choice helped me understand why those in the theater with me during my initial viewing acted like they were watching a different movie than I was: They were under the impression that they were. The fact that I, Tonya was marketed as a comedy is problematic. This genre classification is an oversimplification of a film that touches on powerful and important themes and explores a complex story that many people knew only bits and pieces of and the titular character’s emotional response to the cycle of abuse.

Tonya Harding (Margot Robbie) at the 1994 Olympics in I, TONYA, courtesy of NEON and 30WEST

The story of Tonya’s attempts to cope with a lifetime of mistreatment is the story of I, Tonya, but the marketing and genre classification choices surrounding the film did it an injustice. I, Tonya created a cinematic space in which we had a chance to take Tonya Harding seriously and explore the complexity of women’s emotions surrounding domestic violence. It talked about these issues in a brazen and brave way that we aren’t used to. Much like Harding herself, it was more than it was made out to be, and was promoted in a way that didn’t give it enough credit for its intricacy and strength.