Her Exhibition

Meret Oppenheim’s Retrospective at MoMA

Meret Oppenheim was many things, many artists, many abilities. She was not just the creator of the famous fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon, aka, Object (1936). She was not only the surrealist we know today. She had a history, a personal artistic evolution: as a profound individual, a champion and inspiration for women artists everywhere. Her retrospective at MoMA enlightens the viewer as to where she came from, all the different mediums she explored, and where she ended up. The title My Exhibition honors her very detailed designs for a lifetime retrospective that she envisioned for herself. These designs are prominently displayed as the centerpiece for the exhibit, and the curators have implemented much of what Oppenheim has envisioned. Childless throughout her life, behold Oppenheim’s offspring: her life’s work.

Meret Oppenheim. Object (Objet). 1936. Fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon. Cup 4 3/8″ (10.9 cm) in diameter; saucer 9 3/8″ (23.7 cm) in diameter; spoon 8″ (20.2 cm) long, overall height 2 7/8″ (7.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase

The exhibition includes Oppenheim’s first ever oil painting, Sitting Figure with Folded Hands, (1933). In presenting a figure without gender, Oppenheim reveals an open mind toward the future, as identity itself — and its actions — are as limitless as the anonymous universe in one’s imagination. It is the work of an artist in waiting, holding the inspiration of a lifetime yet to be experienced. Even her actual tools are yet to be committed to, with Sitting Figure having been painted with the artist’s fingers rather than with brushes.

Meret Oppenheim. Sitting Figure with Folded Hands (Sitzende Figur mit verschränkten Fingern), 1933. Oil on cardboard, 18 1/8 × 15 11/16" (46 × 39.9 cm). Kunstmuseum Bern. Meret Oppenheim Bequest

Drawings from Oppenheim’s teenage years, Dream (1928-30) and Daydream (1929), almost harken to a medieval style, possibly inspired by poring over centuries-old books such as the medieval Guttenberg Bible; or perhaps dreaming of them.

Rebellion of formal education and the inability to follow tradition resulted in Oppenheim’s Schoolgirl's Notebook, (1930). A notebook she gifted to her father, it was published in a surrealist magazine in 1957 by Andre Breton.

Daphne and Apollo (1943), a large piece done during World War II, renders mythical figures as surrealist-inspired vegetables. This is unbridled sexuality put on display with these iconic individuals reduced to personality-less objects. At least Daphne appears somewhat human, whereas Apollo seems to be a conglomeration of phalluses: reduced to a mere overly active sexual organ.

Installation view of Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from October 30, 2022 – March 4, 2023. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar. Daphne and Apollo pictured in the middle of the left-hand wall.

Genevieve Hovering over the Water (1957) has the feeling of a found object. It looks like a random panel of wood with a gaping hole, representing Genevieve reduced to an abstract shape. Abstraction was at its height in the 50s, and Oppenheim injected her unique sense of Surrealism into the genre. It's as if Oppenheim saw herself as a lone, floating, undeveloped entity, occupying the limitless realm of abstraction.

Miss Gardenia, (1962) plays with the idea of portraiture itself. The sitter’s face is reduced to a solitary form —the nose — with the suggestion of gardenias throughout the piece honoring the namesake of the subject. Or, it could be the essence of the subject, as Miss Gardenia's very existence is struggling to break through the boundaries of the canvas. Like Oppenheim’s first oil painting, the faceless suggestion reveals a continually regenerating, evolving awareness of self and creation. The future is blank and unformed, holding vast mysterious potential.

Installation view of Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from October 30, 2022 – March 4, 2023. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar. Six Clouds on a Bridge is on the leftmost plinth.

Six Clouds on a Bridge (1975) solidifies the lighter-than-air phenomenon of clouds. It's a sculpture that encapsulates the whole of Oppenheim's career: not only her early surrealist pictures but also the objects she created — either found or manufactured — and her performances, as the sculptures resemble actors or dancers on stage. The binaries of inanimate and animate, objective and subjective art become merged in this work. Surrealism and abstraction, like Apollo and Daphne, come together with their offspring manifesting in this hybrid form.

Meret Oppenheim. New Stars (Neue Sterne). 1977–82. Oil on canvas. 6 ft. 8 11/16 x 8 ft. 1 13/16 in. (205 x 248.5 cm) Kunstmuseum Bern. Meret Oppenheim Bequest

If Six Clouds on a Bridge is a sculptural review of Oppenheim’s career, then New Stars (1977) is a large-scale painterly amalgamation of all of her accumulated knowledge. The surreal geometric abstraction of the stars is set against the expanse of the landscape underneath. These elements reflect the pregnancy of personal and universal history embedded within the subtle tactility of the painted sky and landscape. Harkening back to the open-ended faceless portrait seen earlier in the exhibit, Sitting Figure with Folded Hands, it all comes full circle. The sky that the faceless being looks up into, in imagination, could very well be this piece.

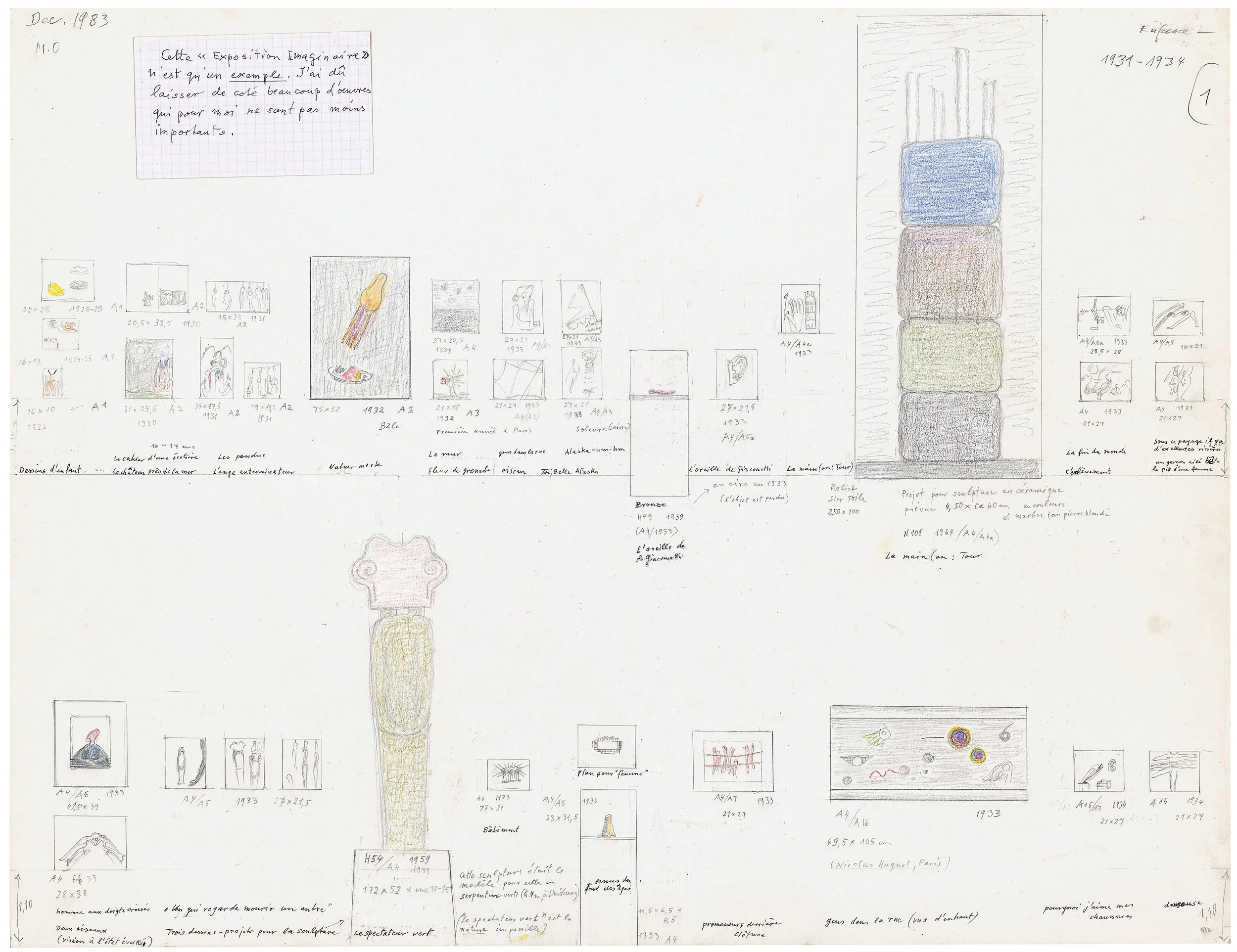

Meret Oppenheim. M.O.: My Exhibition (M.O.: Mon Exposition), 1983. Pencil, colored pencil, and ballpoint pen on twelve sheets, 25 1/2 × 19 11/16" (64.8 × 50 cm). Bürgi Collection, Bern

The centerpiece of My Exhibition is a series of drawings on large sheets of paper made in 1983. The pictures, by virtue of indicating an "Imaginary Exhibition" (Oppenheim's own words), are a series of surreal pieces themselves, a tapestry of articulated personal language. It is a sentence in a life developing not just surrealism, but self-realization: an independent free-thinking woman who challenged not only gender but the shape of reality itself. As a book, an autobiography can only relay events. But these pictures within pictures reveal the form, atmosphere, and imagination of a profound thinker of the 20th century. These drawings are the artistic intimacies of Oppenheim's mind and a tremendous reconsideration of her whole life. She was a lifelong performer, even portraying a curtain in a play she helped design. The drawings, along with the realized retrospective, are the theater of her well-worn hand as an artist. We applaud at the reveal.