“Visually Sated Yet Cognitively Deprived”

Lucretius, just before describing the infinite universe in De rerum natura [On the nature of things], writes that most people are fessus satiate videndi, weary from satiety of seeing, and therefore unable to see how wonderful the universe really is.[1] One can only imagine what the Epicurean poet might think about the state of seeing in today’s media-rich world, one that leaves viewers visually surfeited yet largely incapable of making sense of the pixelated slop consumed day in and day out. Visual Implications, curated by Ashley Ouderkirk, engages with these interrelated themes of visual consumption, perception, patterns of seeing, and the importance of visual literacy by presenting the work of three emerging artists: Charles Clary, Nanse Kawashima, and Cassandra Zampini. Elaborated across two venues (a Chashama space in Manhattan and Kunstraum Gallery in Brooklyn) and over two-hundred paper-cut, printed, video, and painted works, the exhibition showcases the artists’ divergent pictorial strategies for engagement and critical self-reflection.

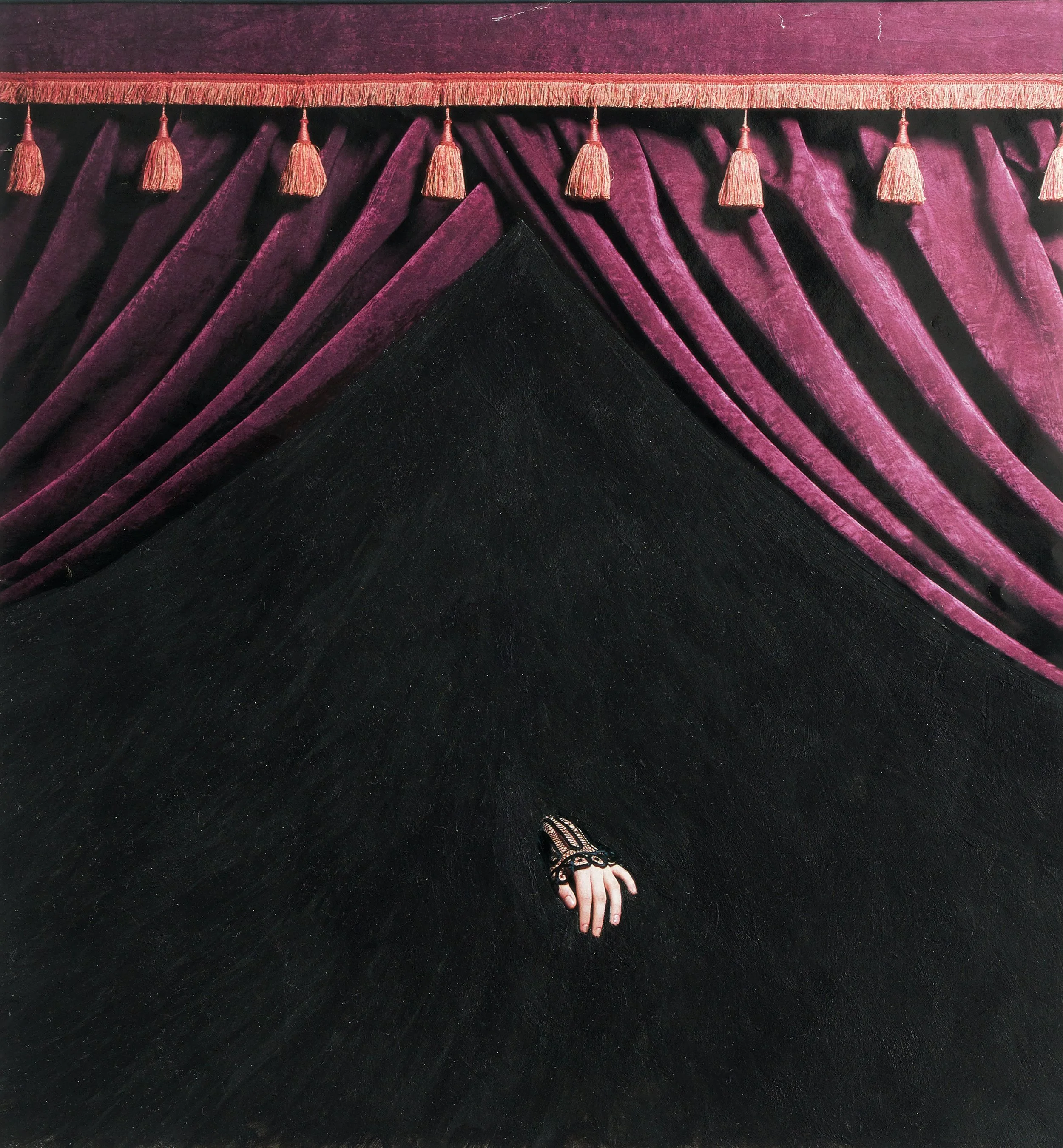

Nanse Kawashima, Man Hand, 2018, Acrylic on printed paper, 6.25 x 7.69 in.

Nanse Kawashima’s esoteric works on paper, arranged on the wall in a manner similar to how a tarot card reading would be performed, both entrance and confound viewers. The artist mines the rich folklorist and religious traditions of the locales she has lived in, such as Japan, Guatemala, Hawaii, Jamaica, and Brooklyn. With references to global mythologies, species of flowers, and astrology, each work allows spectators “to flex their visual literacy by recognizing familiar gestures, symbols, and icons...”[2] Kawashima’s intimate works feature disembodied body parts—hands, eyes, heads, torsos—situated within pitch-black voids, perhaps cryptic visions being conjured before the beholder. Works like Man Hand (2018) and The Hand (2016) recall Albrecht Dürer’s Self-portrait with Fur-trimmed Robe (1500), where the consummate German Renaissance artist famously linked hand and mind—contending that artists are purveyors of ideas as well as pictures.

Nanse Kawashima, The Hand, 2016, Acrylic on printed paper, 8.63 x 8 in.

Albrecht Dürer, Self-portrait, 1500. Oil on wood panel, 26 ¼ x 19 ¼ inches (66.3 x 49 cm). Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

In Magma (2022), one of the most compelling works in the exhibition, staccato strokes of cream, peach, maroon, salmon, and orange are applied in all directions and form an indefinite, ominous cloud. On the periphery, the taches are distinct, but approaching the green eyes in the center the marks become blended. Here, the site where the mind is materially inscribed, the mark of the artist is fused with a symbol of sight, reminding us that images are not neutral. Rather, like magma coursing below the Earth’s crust, beneath every image is a core logic reflecting the ideologies and orientations of its maker. These worldviews are not contained by the frame, but freely flow into surrounding contexts.

Nanse Kawashima, Magma, 2022, Acrylic on printed paper, 10 x 7.81 in.

Similarly, Wave (2020), the title image for the show, contains three half-closed, greenish-blue eyes staring out directly at the viewer in a tempest of white, blue, and yellow streaks of acrylic. In contrast to the pair of eyes looking obliquely in Magma, in Wave guests are directly implicated. It is important to note that Wave has been painted over vintage print media, suggesting that visual communication has eroded the primacy of written communication. As a Homeric beacon, in our unresolved odyssey through the sea of images, Wave calls us to seek enlightenment, revelation, and illumination, lest we be lulled by the siren songs of Alex Jones and his ilk, which can be faintly overheard in the distance.

Nanse Kawashima, Wave, 2020, Acrylic on printed paper, 14 x 11 x 1.38 in.

Set within a viewing booth, Cassandra Zampini’s NFT video, MediaWarfare (2020), simultaneously plays countless videos she culled from online sources, ranging from vaccine misinformation campaigns to anti-Semitic rants about adrenochrome. In a cacophony of falsehoods, the artist cuts to the heart of the matter: the majority of the world is visually illiterate, which is compounded by an overwhelming mistrust of public institutions. Zampini’s new media works comment on how large swaths of the American public are unable to suss out truth from half-truth from bold-faced lies manufactured in media silos and then filtered by the algorithms above, like grade-A Silicon Valley animal feed distributed on Jones’s Manor Farm.

Cassandra Zampini, MediaWarfare, 2020, NFT video

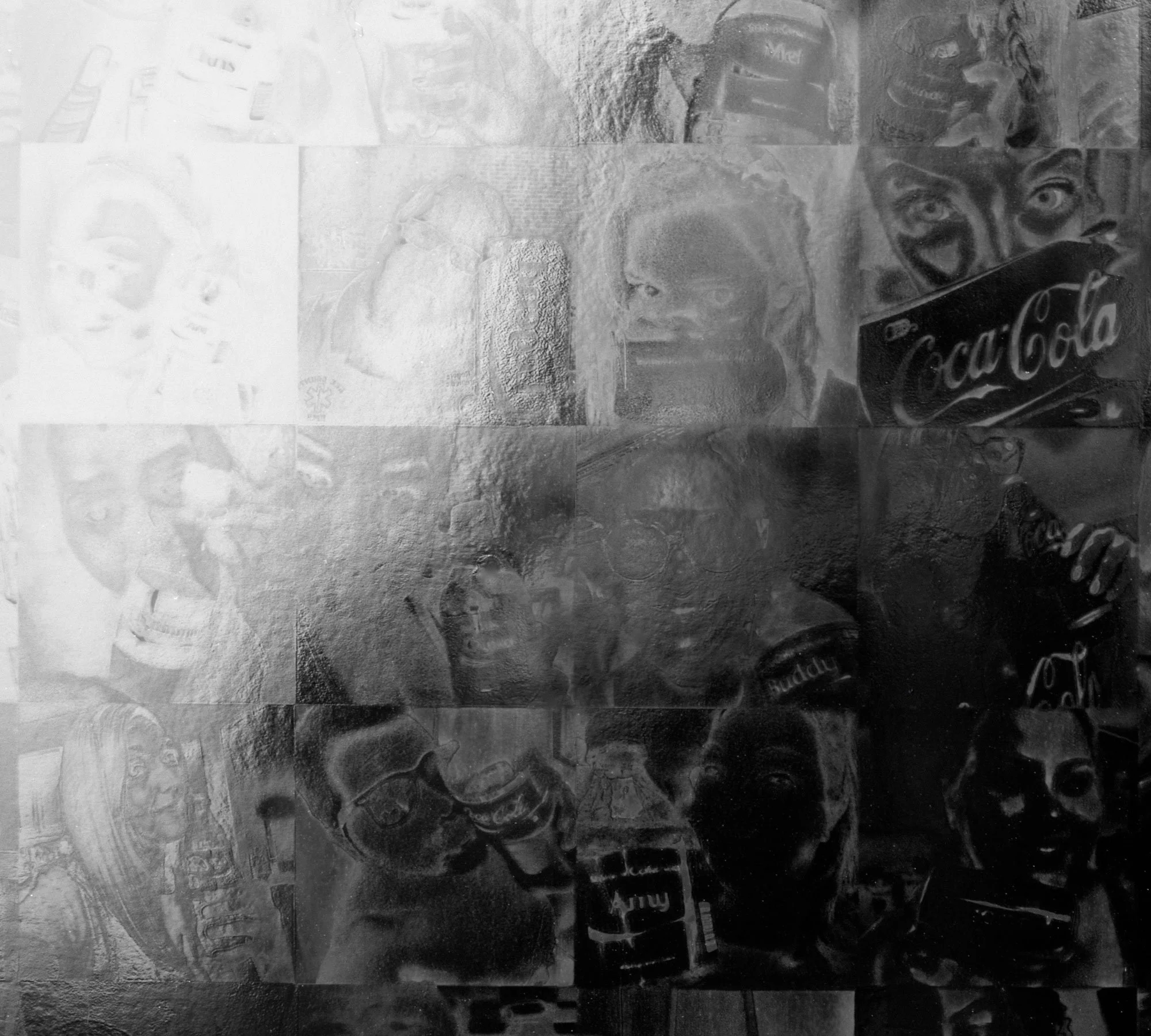

Nearby are thematically linked archival pigment prints, #Flex_1sec (2018), #preggo_1sec (2018), and #youcantbeatthefeeling (2022)—all of which point to the phenomenon of online trends, hashtags, indexing, and virality through the titling. Each digital shard of the 2018 monochrome photo mosaics portrays an individual either flexing in a self-portrait or posing with a baby bump, with the top and bottom edges of the grid dissolving. I see a connection between Kawashima’s analogic mark-making and Zampini’s digital compositions. Whereas the former communicates her tarot-inspired auguries in an indirect manner, the latter conveys her social commentary in a more straightforward mode, pastiching together recognizable poses and expressions that draw the viewer in.

Cassandra Zampini, #Flex_1sec, 2018, Archival pigment print mounted on Dibond, 63.5 x 38.5 in., Ed. 3 of 3

In #preggo_1sec, the black-and-white photos brilliantly illuminated in the middle of the composition actually bulge. While this distended mass of collaged images references the titular fad, the bloated composite also speaks to the weight of the sheer volume of uploaded selfies and the oversaturated mediascape we must navigate. These works also bring out memories of textbook covers or memorials that make use of photo mosaics to convey a sense of diverse lived experiences, but also a larger sense of unity. Perhaps, too, Zampini’s works can serve a didactic purpose that leads to critical self-reflection in a society that is embarrassingly self-absorbed and enamored of the short-lived surface.

Cassandra Zampini, #preggo_1 sec, 2018, Archival pigment print mounted on Dibond, 63.5 x 38.5 in., Ed. 1 of 3

If Zampini’s video and prints criticize superficiality and a wide-spread lack of critical thinking, then Charles Clary directs the viewer’s gaze downward and inward to the depths of childhood memories. At the Chashama venue, his series “Be Kind Rewind” (2019-22) takes up a large portion of the space. The idea of documentation or cataloging seen in Zampini’s work resurfaces in the form of a personal video rental store. Ranged along the wall are VHS cassette sleeves of movies he has cut into, carving out multi-colored cells or compartments. The paper-cut incisions are lyrical, having an upward pull or swell, like pop culture spermatozoa squirming beneath the surface suggesting how movies are both ideologically pregnant and in turn inseminate values, ideas, beliefs, and attitudes in consumers.

Cassandra Zampini, #youcantbeatthefeeling, 2022, Archival pigment print mounted on Dibond inked by artist post-printing, 56 x 28 in., Ed. 1 of 3

Standing in front of this non-circulating, cathartic Blockbuster display, this is another pivotal moment where the visual acuity of exhibition-goers is tested. Depending on your rental history, the covers of Poltergeist II, Rambo, Shrek, and many others elicit mixed memories and emotions—and the cellular paper-cut patterning similarly evokes many departure points for meaning: topographical maps, terraced agriculture, muscular or vascular tissue, and abstract designs. The impetus behind this staggering series of deeply vulnerable works is Clary’s attempt to grapple with traumatic aspects of his childhood, namely abandonment, parental absenteeism, and the void popular culture played in filling that absence.

"Charles Clary: Be Kind Rewind Series (2019-2022)" installation view at ChaShaMa, Photo by Garland Quek

Like Kawashima’s Magma, these works encourage spectators to see images and cultural signs as having active interiors, functioning according to a specific viewpoint but whose meaning is not wholly determined by its creator. Our responses to art are learned behaviors informed by class, race, gender, geography, and a host of other categories of identity. As such, as Jules Prown has argued, art “can arouse different patterns of response according to the belief systems of the perceivers’ cultural matrices.”[3] What’s more, his works dealing with compartmentalizing emotional pain dovetail with some of Kawashima’s paintings about privacy, secrets, and interiority. For instance, in her Tiers of Secrecy (2018), four black trunks are stacked on top of one another with an omniscient eye hovering above, surrounded by sgraffito in white acrylic paint radiating outwards. Kawashima’s painted eyes and Clary’s colorful yet deep wounds are inescapable in this exhibition, each serving as a portal for introspection.

"Charles Clary: Be Kind Rewind Series (2019-2022)" installation view at ChaShaMa, Photo by Garland Quek

The other half of the exhibition based at Kunstraum, solely focused on Clary’s “Memento Morididle Movement” series (2019-22), might be taken as the other side of these portals. The crimson walls and salon-style hang have an immediate visual impact, giving the impression of entering a nineteenth-century antechamber. This design decision is fitting since the nineteenth century witnessed new discoveries and theories about the nature of vision, color, and perception (i.e. Michel Eugène Chevreul and Hermann von Helmholtz). Instead of seeing a hierarchy of the genres arrayed on the wall—as would be customary at the French Salon—one finds theme and variation played out across ornate wooden and metal frames in hexagonal, ovoid, circular, and rectangular formats.

Like the smaller works in the “Be Kind Rewind” series with psychological excavations, these framed works additionally include various wallpapers, anatomical diagrams, kitschy flamingo designs, and organic imagery (skulls, mushrooms, pine cones, butterflies, and flowers). The extensive use of wallpaper reinforces the nature of Clary’s work since it indexes domestic spaces—sites where our views are shaped. Further, the fecund and macabre images relate to the series’ namesake, the Latin phrase used as a reminder of death and the fleeting nature of life. While verging on optically overwrought, Clary’s “maximalist paper sculpture installation” is nonetheless a feast of visual delectation, underscored by one work surmounted on an antique serving platter.

"Charles Clary: Memento Mori series (2019-2022)" installation view at KUNSTRAUM, Photo by Garland Quek

On the balance, Visual Implications is a sensitively organized and conceptually robust show. It is a playground or gym for the eye and mind. Fitting for a show about the multivalent nature of images, the title might be read in several ways: to discern between competing inferences; to consider the consequences of how images mediate human relationships and power dynamics; and how viewers themselves are implicated in contemporary visual networks of exchange. Among many reasons, this exhibition can be commended for its ability to put these timely questions in motion and generate a variety of answers through the works on view. Chief among my few critiques is that the works of individual artists could have been more integrated to create unexpected visual and semantic play. For instance, placing one or more of Clary’s paper-cut VHS sleeves beside one of Zampini’s photo mosaics would have brought out ideas about the formation of self in the analog and digital eras. In the end, Ouderkirk asks us to weigh the visual implications, meaning to perceive or judge, but to render a judgment one must first be able to read the visual text. To my mind, we would do well to heed Lucretius’s plea: “Wherefore cease to spew out reason from your mind, struck with terror at mere newness, but rather with eager judgement weigh things, and, if you see them true, lift your hands and yield, or, if it is false, gird yourself to battle.”[4]

[1] Titus Lucretius Carus, Book II, D. “The Infinite Worlds and their Formation and Destruction,” (2.1038.), On the Nature of Things, trans. Cyril Bailey (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1910).

[2] Kunstraum, “Visual Implications,” press release, January 19, 2023, https://www.kunstraumllc.com/single-post/visual-implications, accessed 25 January 2023.

[3] Jules Prown, “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method,” in Art as Evidence: Writings on Art and Material Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 77.

[4] Titus Lucretius Carus, Book II, D. “The Infinite Worlds and their Formation and Destruction,” (2.1040-43), On the Nature of Things, trans. Cyril Bailey (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1910).